People will always look different

from each other in ways we can’t

control. What we can control is

what we allow ourselves to make

of those differences.

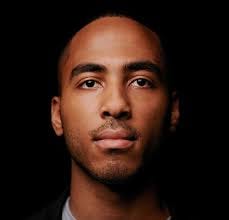

--Thomas Chatterton Williams

I have two index cards taped to my computer monitor. The one on the left contains William Zinsser’s four principles of good writing:

Clarity

Simplicity

Brevity

Humanity

The index card on the right contains the “four agreements” laid out by Don Miguel Ruiz in his book, The Four Agreements: A Practical Guide to Personal Freedom:

Be impeccable with your word

Don’t take anything personally

Don’t make assumptions

Always do your best

The first agreement, the author informs us, is the most important.

The word is the most powerful tool you have as a human; it is the tool of magic. But like a sword with two edges, your word can create the most beautiful dream, or your word can destroy everything around you. The word is pure magic—the most powerful gift we have as humans—and we use it against ourselves. We plan revenge. We create chaos with the word. We use the word to create hate between different races, between different people, between families, between nations…We can either put a spell on someone with our word or we can release someone from a spell.

The End of Race Politics, by Coleman Hughes, is an example of someone using the word to create a beautiful dream, the dream of a colorblind society. It is, in large part, a response to writers such as Robin DiAngelo and Ibram X. Kendi who use the word to persuade people that we live in a country defined by white supremacy. They call themselves antiracists. Coleman Hughes calls them neoracists.

Despite our fifty-year age difference, Coleman Hughes and I share a few things in common, including a love of jazz and degrees in philosophy. I also share Coleman’s emotional reaction to what has transpired in our country vis-à-vis race:

“When I look at the current racial landscape of American society, I feel sick at heart.”

That is exactly how I feel whenever I read or hear someone claiming that there has been no progress since the civil rights movement. Or when I read the words of Robin DiAngelo in her bestselling book, White Fragility, claiming that every white person in America is racist. Or when I read so-called race experts like Ibram Kendi proclaiming that the only way to correct the racial injustices against blacks in the past is to implement racist policies against white people today.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not violating Ruiz’s agreement about not taking anything personally. I am not a fragile white guy whose tender feelings are hurt when some white female charlatan labels me a racist. What disturbs me is the same thing that disturbs Coleman Hughes, who writes, “If these ideas were confined to high school conferences and Ivy League universities, one could make the case that they are not worth worrying about. But they have infected all of our key institutions: government, education, and media.”

Growing up in the 1990s and early 2000s, Coleman Hughes did not experience the kind of systemic racism that was going on when I was a youngster in the 1950s and early 1960s. For example, there were three movie theaters in Springfield, Missouri, two of which denied admission to black people. The third one, the Landers Theater, allowed blacks admission only on certain days. But they were never allowed to sit in the auditorium. They had to sit in the balcony.

There is no need to go into all the injustices imposed on black people during the Jim Crow era and eliminated by the time Coleman was born. They are well-documented. But it’s interesting to note the difference between our experiences growing up. Coleman writes:

For most of my young life, I rarely thought about my racial identity. I had black friends, white friends, Asian friends, Hispanic friends, and mixed-race friends. But I didn’t think of them as ‘black,’ ‘white,’ ‘Hispanic,’ and ‘mixed race.’ I thought of them as Rodney, Stephen, Javier, and Jordan. For the most part, the people I grew up around seemed to share my lack of interest in race. They agreed with Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous dictum about the content of one’s character trumping the color of one’s skin—even if collective overuse had already made it a cliché.

The protagonist in my novel, Redbirds, is Jordan Langston. Two aspects of Jordan’s story mirror my own story: his Vietnam combat experience and his decision to major in philosophy in college. There is a passage in which Jordan and his grandmother, Lucinda Langston, are driving from the family farm in Arkansas to the medium-security prison in Moberly, Missouri to speak on behalf of a character named Levi James at his parole board hearing. Levi, a black man who grew up in St. Louis, served with Jordan in Vietnam. They were both sergeants, leading two of the platoon’s three squads.

After the war, while Jordan is working on his doctorate in philosophy, and Levi is training Marine recruits at Parris Island, Levi is informed that his mother died as a result of falling down concrete steps outside their apartment in the projects. Levi correctly assumes that his father, a violent alcoholic, was responsible for her death. He immediately drives straight to St. Louis from South Carolina and beats his father to death.

During their drive to Moberly, Jordan tells Lucinda how the war changed his life.

“Grandma, you mentioned the difference between Dad’s war [WW2] and mine. One difference that is usually overlooked involves race. The Marines Dad fought with were all white.”

“That’s true. The services weren’t integrated until Truman made it law in the late 1940s.”

“Had I not served in Vietnam, I probably would have marched for civil rights because it was the fashionable thing for white liberals to do. It would have made me feel good about myself.”

“But?”

“But deep down I would still have regarded skin color as a defining characteristic of human beings. Unlike civilian life, there was no social distance between whites and blacks in the combat zone. We were all one, all of us sharing the same goal: survival. The experience led me to the conclusion that race is a myth.”

That is my lived experience. My lived experience, however, means nothing to Robin DiAngelo. A whole chapter of her book is devoted to dismissing every conceivable reason white people offer against the charge of racism. DiAngelo divides them into two categories—colorblind and color-celebrate. Examples of the former include, “Race doesn’t have any meaning to me,” “Focusing on race is what divides us,” and “If people are respectful to me, I am respectful to them, regardless of race.” Color-celebrate claims include, “I am married to a person of color,” “I live in a very diverse neighborhood,” and “My parents were not racist, and they taught me not to be racist.”

DiAngelo examines each of these claims, explaining why they are all irrelevant. For instance, here is her take on the claim, “My parents were not racist, and they taught me not to be racist”:

Your parents could not have been free of racism themselves. A racism-free upbringing is not possible, because racism is a social system embedded in the culture and its institutions. We are born into this system and have no say in whether we will be affected by it.

In short, all white Americans are racist because they were born into a racist country. A visitor from a foreign country might wonder how someone can become a millionaire in America by persuading white people that they are, independent of their thoughts, words, and actions, racist. Shelby Steele has an answer. Steele is an author, columnist, and documentary filmmaker who knows a thing or two about actual racism:

I grew up in the rigid segregation of 1950s Chicago, where my life had been entirely circumscribed by white racism. Residential segregation was nearly absolute. My elementary school triggered the first desegregation lawsuit in the North. My family was afraid to cross the threshold of any restaurant until I was almost twenty years old. The only jobs open to me in high school were as a field hand or as a yard boy. My high school guidance counselor said flatly that manual labor would be my employment horizon. My life had to always be negotiated around my failure to be white.

Steele’s explanation of why so many people have bought into the neoracism of Robin DiAngelo and others is white guilt, which he defines as “the terror of being seen as racist—a terror that has caused whites to act guiltily toward minorities even when they feel no actual guilt.”

In his book, Shame: How America’s Past Sins Have Polarized Our Country, Steele characterizes white guilt as “a smothering and distracting kindness that enmeshes minorities more in the struggle for white redemption than in their own struggle to develop as individuals capable of competing with all others.”

Contrast Shelby Steele’s upbringing with that of Coleman Hughes. Growing up in Montclair, New Jersey, Coleman attended public schools until the sixth grade when his parents enrolled him in Newark Academy which he describes as “a fancy private school several towns away.” During his fourth year there, at the age of sixteen, Coleman was offered the opportunity to attend a three-day event in Houston called the People of Color Conference:

Misleadingly, the conference was not just for people of color but for private school students of all races—hundreds of us from around the nation. Though I wouldn’t have known to call it this at the time, the conference was essentially a three-day critical race theory and intersectionality workshop. It was there that I first heard terms like systemic racism, safe space, white privilege, and internalized oppression—ideas that were fringe in 2012. At the conference, my blackness was not considered a neutral fact—irrelevant to my deeper qualities as a human being…After my brief foray into the strange, race-obsessed world of the POC Conference, I returned to my life as a high school student who cared about music and philosophy, and who connected with others on the basis of shared interests rather than race. I never imagined that the subculture I encountered in Houston would appear in my life again.

Unfortunately, Coleman discovered he was sadly mistaken about that when he enrolled at Columbia University:

In four years at Columbia, hardly a week passed without a race-themed controversy. In the school newspaper, students would say they experienced white supremacy ‘every day’ on campus. A professor of mine once told our class that ‘all people of color were by definition victims of oppression,’ even as my daily experience as a black person directly contradicted that claim...Though I found the topic of race to be boring in and of itself, the surrounding culture was obsessed with it—and was hell-bent on dragging me in.

Hughes believes in the colorblind principle. He makes it clear that colorblindness is not a synonym for the absence of racism, but rather, an ideology created to combat racism. He hopes his book will help “restore our faith in the guiding principle of colorblindness and pave a constructive path forward in our national conversation on race.”

It’s important to understand what Hughes means by colorblindness—and, for that matter, what I mean by it when I say that I became colorblind in Vietnam. First, it is important to understand what it does not mean. Colorblindness does not mean becoming blind to the appearance of race. For instance, during my first Vietnam tour of duty, my two fellow squad leaders were Jose Perez from San Antonio and Freddie Carradine from Compton, California. Becoming colorblind did not mean I no longer noticed that Carradine’s skin was black and Perez’s brown. It meant that my perception of them was based on our common humanity and the need to work together harmoniously in the continuous effort to keep ourselves and the Marines we led alive.

“At this moment in American history,” writes Hughes, “we have a choice. We can follow neoracists down the path of endless racial strife, or we can recommit ourselves to the principles that motivated the civil rights movement…Those principles include colorblindness—the idea that we should treat people without regard to race, both in our public policy and in our private lives.”

Coleman Hughes is not naïve. As he stated in an interview, “I’m under no illusion that humanity will completely eradicate the racial tribal instinct or racism or bigotry itself. But I feel that colorblindness is the North Star we should use in making decisions.”

Hughes traces the historical importance of the colorblind principle back to the abolitionists. “Colorblindness,” he writes, “was a key goal in the anti-slavery movement and the main goal of the civil rights movement. It was not invented [as neoracists claim] by conservatives or by racists. Rather, it was invented by the most radical anti-racist activists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and abandoned by the so-called anti-racists of our era.”

Hughes cites a quote from Frederick Douglass, a man born into slavery, who taught himself to read and write, became the main figure of the abolitionist movement, and wrote three books:

I conceive there is no division of races. God Almighty made but one race. You may say that Frederick Douglass considers himself to be a member of the one race which exists.

When asked if he fought for black people because he was black, Douglass replied, “If I have advocated the cause of the colored people, it is not because I am a negro, but because I am a man. The same impulse which would move me to jump into the water to save a white child from drowning causes me to espouse the cause of the downtrodden and oppressed wherever I find them.”

Hughes writes, “Dr. King would often express the same idea, usually framed in religious language. ‘Racial segregation,’ he wrote, ‘is a blatant denial of the unity which we have in Christ; for in Christ there is neither Jew nor Gentile, bond nor free, Negro nor white.’”

Hughes has a lot to say about the neoracists' demand for racial equity:

Neoracists imagine that if we enact discriminatory policies for long enough we will finally balance the scales of history. We will be able to undo the past, give back to blacks what was taken from them for hundreds of years, and reach a state of racial ‘equity.’ But this is a dangerous fantasy.

It’s not that Coleman Hughes opposes public policies designed to help the disadvantaged. On the contrary. He favors policies that help all disadvantaged people, which is why he is in favor of class-based policies instead of race-based policies.

Imagine that we picked one hundred Americans at random. Our task is to line them up from ‘least privileged’ to ‘most privileged’ so that we can use public policy to prioritize the least advantaged among them. Because there is no direct measure of privilege, we would have to choose a proxy. My claim is that lining everyone up by socioeconomic status—income, wealth, or some combination measure—would get us closer to our goal than lining them up by racial identity would. That is what I mean when I say that income is a better proxy for disadvantage than race.

The foregoing is just a bare-bones examination of Coleman Hughes’ extraordinary book. I encourage everyone to pick up a copy.